On gladsome occasions they perform the Te Deum laudamus not merely out of ceremony, as in many other places, but out of real fervour for the honour and glory of God, occasionally and commonly to the sound of trumpets and drums, and occasionally even with the firing of canons; otherwise what a particular author wrote of these songs of praise is, sadly, more often than not true in certain places: in the morning they sing out loud, We praise thee 0 Lord, in the afternoon their actions say, We devour to thee, 0 Lord, We drink to thee, 0 Lord, We dance to thee, 0 Lord, We play operas and comedies to thee, 0 Lord.» (Julius Bernhard von Rohr «Ceremoniel-Wissenschaft / Der grossen Herren … Berlin 1733)

However that may be, sacred music in the baroque era was a considerable representative element not only for the highest of the land; each sacred or secular prince possessed a church building whose size, together with the degree of magnificence and splendour of its music, reflected his importance. Equally, it was almost inevitable that princely trumpets should be included in the celebration of a high religious feast. Use of these solemn instruments in praise of God also suggested a merging of earthly and heavenly powers, an obvious display of absolutism.

Like his predecessors Ferdinand III, Leopold I, Joseph I and other Habsburg rulers before and after, Karl VI held music in great importance. The archives still overflow today with the amount of music which sounded in the orchestra pit and musicians’ gallery, in the state rooms and chambers of his Majesty the Prince Regent. That which has been discovered up until now, whether sacred or secular, gives but a glimmer of the musical splendour which surrounded Karl VI.

Church music at the court of Karl VI was produced in the first instance by the two directors of music, JOHANN JOSEPH FUX and Antonio Caldara. Fux, court music director, composed over 400 sacred works including 90 complete masses, all the more surprising given that the Styrian suffered badly from gout since his fifties. Incidentally, Fux wished his works to be performed with «natural expression», meaning without the ornaments and variations usually added by singers and instrumentalists of the time, a practice Fux deplored: there was no need to add «countless variations to a piece simply because the performer wishes to show off more than necessary, even insufferably»,

Altogether, three complete settings of the TE DEUM by Fux have survived. The inscription PER LA CORONAZIONE» on the cover of the parts of the Te Deum K 270 as well as its «solenne» instrumentation suggest that this is the work mentioned in a description of the festivites of 1723 in Prague celebrating the coronation of Karl VI as King of Bohemia: the archbishop, standing next to His Majesty’s throne, «intoned the Te Deum laudamus which was then taken up by the entire company of musical instruments, including trumpets and drums». It is impressive how Fux managed to write more than just solid ceremonial music, portraying the text in the smallest detail. Homophonic passages contrast with arioso sections and there are frequent changes of affect. The piece, ending with a fugue on «In te, Domine, speravi», gives a brief impression of the Vienna court’s answer to the French «Grands Motets».

ANTONIO VIVALDI, like Johann Joseph Fux, died in Vienna in 1741. Was he simply travelling through or was he in search of a new patron? We do not know for sure, but the fact remains that the «red priest» was in contact with Karl VI. In September 1728 the Emperor spent a few days in Triest, travelling in connection with an oath of fealty, and gave a Venetian legation audience there. Vivaldi was among the followers of this dele gation, and it is reported that Karl VI «presented Vivaldi with a great sum of money as well as a golden chain and made him a knight».The emperor and composer are said to have conversed at length about music and «it is said that he spoke more with him in two weeks than with his ministers in two years».

In his heyday, the famous composer and violinist Vivaldi worked as Maestro di Capella at the Ospedale della Pietà, one of four girls’ orphanages in Venice. Tourists from far and wide flocked to the city to hear the Ospedale orchestra and its famous leader, the «prete rosso», or red-headed priest. Vivaldi was the ultimate reference in matters of Italian taste for a considerable number of musicians from German lands. He received a yearly salary of 100 ducats from the direction of the Pietà as well as an additional salary especially for composing new works. Vivaldi’s sacred music remains almost unknown today. Yet during his lifetime, it was this genre in particular that was greatly valued and the reason for extra payments made to the Venetian composer.

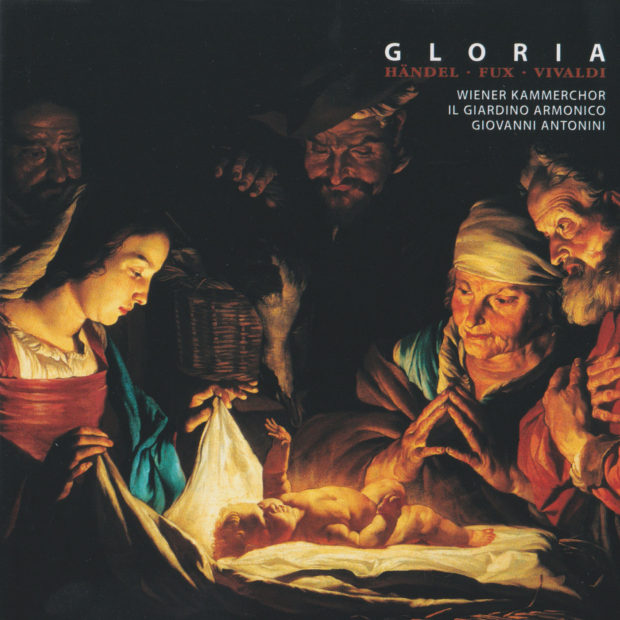

His setting of the «GLORIA» RV 589 has long been a favourite in modern times. It was probably composed in 1716 to celebrate the victory against the Turks by the Habsburgers and their allies, including Venice, led by the famous Prince Eugen.Vivaldi used a trumpet in an almost concertante role in addition to an oboe for this festive work. This imposing work serves to illustrate better than almost any other the many facets of Vivaldi’s genius, ranging from arias that could have come straight out of an opera to fugally worked-out choruses,

GEORG FRIEDRICH HANDEL, known to the Italians as «Caro Sassone», enjoyed great success in Rome, Venice and Florence — he may even have had contact with the «Prete rosso».In any case he was courted in Rome by the great patrons of the arts, the Cardinals Pamphilij and Ottoboni, as well as by the Marchese Ruspoli. On 13th June 1707 the motet «COELESTIS DUM SPIRAT AURA», a work «IN FESTO S. ANTONII DE PADUA», was performed at Ruspoli’s country residence Vignanello. It takes the form of a typical Italian cantata and contains references both to the 475th anniversary of the canonisation of St. Anthony, on which occasion it was first heard, as well as to the «Julianellum», the original name of Ruspoli’s castello, now called Vignanello.

Handel refers back to his youthful Italian years once more in the concerti that he wrote in London, specifically to the splendid concerti of maestro Corelli, who led Cardinal Ottoboni’s orchestra from his devilish violin. Handel would not have been true to himself, however, if he had not infused them with the passions of a life led to the full, spiced with a pinch of German counterpoint, together with many Italian stylistic elements. Cheerful, melancholic and virtuoso, these orchestral works were among the best to be heard in Europe at the time. Handel wrote his Twelve Concertos op.6, an extremely popular collection of concerti grossi, in the space of just one month in 1739.They display more influence of the famous Italian examples than those in the opus 3 collection. Thus the CONCERTO GROSSO OP. 6 NR. 7 is constructed in the form of a sonata da chiesa, ending however with a British hornpipe.

Translator: Roderick Shaw